Building Support for Your Project: Stakeholder Analysis

By Deborah Hopen

A stakeholder is “a person or group that has an investment, share or interest in something…” (Dictionary.com). For team-based endeavors, stakeholders may include a diverse set of individuals, functional departments, teams and other groups that are interested in influencing the project’s direction or will be affected by its outcomes. Taking the time to thoroughly analyze who the stakeholders are and what their issues may be is essential to project success.

A stakeholder analysis should be based on actual data, not on team member assumptions.

Stakeholders can be internal or external to the organization, and may include suppliers, employees and members of the local community. (While also a stakeholder, customers are considered separately because their expectations are generally prioritized higher.) A stakeholder analysis provides a useful mechanism for determining how well different stakeholders support the initiative and what actions may be used to increase their cooperation.

A stakeholder analysis should be based on actual data and discussions with stakeholders, rather than team members’ assumptions. Understanding your stakeholders’ perceptions of and reactions to the project can significantly impact the time required to identify and implement changes. Stakeholder analysis tends to be an underutilized method, and that deficiency can create substantial setbacks for teams who have not incorporated actions for addressing stakeholders’ lack of support.

There are several tools available for conducting stakeholder analysis, and one of the easiest to use is the Stakeholder Map.

This tool is useful for capturing information on stakeholder support, resistance and influence. It helps to create a consensus of how to involve key stakeholders, as opposed to having individual team members rely on their diverse perspectives and actions. The Stakeholder Map is a good tool for quickly identifying where special efforts are necessary to garner support and/or head off resistance.

Steps to Fill out the Stakeholder Map

Download the Stakeholder Analysis Template

- Draw the Stakeholder Map, as shown above. There is no need to add the colors to the nine-block grid at this point.

- List every key stakeholder—whether an individual or group—in the center column of the Stakeholder Identification table. The code in the left column of the table will be associated with each stakeholder.

- Indicate the level of influence each stakeholder has over the change and/or others in the right column of the table.

- Meet with each stakeholder (individual or group) to discuss the project—particularly its background and objective.

- Solicit feedback from the stakeholder (individual or group) regarding perceptions and reaction to the project plan.

- Reach a consensus among the team members on each stakeholder’s ratings for “Impacted by Change” and “Reaction to Change.”

- Indicate the “ID Code” when assigning each stakeholder to the appropriate block within the grid.

- Use red to colorize all blocks where the stakeholder has a high influence, yellow where the stakeholder has a medium influence, and green where the stakeholder has a low influence.

- Add a footnote to the bottom of the diagram that indicates the date of its creation and the name of one or more participants who can be contacted if additional information is needed about the process used to generate the Stakeholder Map. This is a good general practice when creating project documentation.

Example of a Completed Stakeholder Map

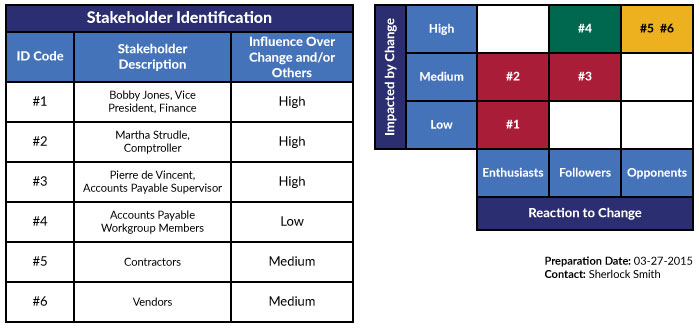

The graphic below shows an example of a stakeholder analysis for a project involving the accounts payable workgroup.

The vice president has been instructed to find a way to increase the organization’s working capital. He has decided that all contractor and vender payments will be delayed—from within the historical 30-day payment timing to between 45 and 60 days.

Because the contractors and venders will have to wait quite a bit longer to receive payments for goods and services, they expressed substantial resistance when interviewed.

The supervisor and members of the accounts payable workgroup were less resistant because they understood the organization’s overall objective, but they still were concerned about the proposed change.

Those with higher authority who had accountability for increasing the organization’s working capital, but who were not in regular contact with the contractors and venders, were very enthusiastic about the proposal.

Tips for Using the Stakeholder Map and Addressing Opposition

When stakeholders do not support the team’s project, they may demonstrate resistance. The approaches shown in the table below provide some tips for counteracting initial opposition. A careful review of the stakeholder analysis can provide insights into which of those actions best fit the existing issues. A variety of approaches may be necessary to address the resistance of different individuals and groups.

| Approaches for Addressing Resistance | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category and Causes of Resistance | Suggested Approaches | |

Technical

|

| |

Political

|

| |

Cultural

|

| |

Once the Stakeholder Map is prepared, it can be used as the foundation for other analyses, such as the development of a communication plan for team members to follow throughout the project. If the stakeholders are kept well-informed about the project’s progress and how it is affecting the organization’s performance, they often will become more supportive. That’s why revisiting the Stakeholder Map several times during the project can be very worthwhile.

For a Lean Six Sigma project, it can be particularly useful to share the results of the Analyze Phase’s determination of root causes along with the results of the piloted solutions in the Improve Phase. In many cases, helping the stakeholders understand the findings for these two phases can switch their mindsets and generate commitment to the full-scale implementation of the solutions during the Control Phase.

A Coach’s Perspective

Many new teams seem to underestimate the value of stakeholder analysis. Team members often are excited about contributing to organizational performance by solving problems, identifying strategies for meeting changing requirements, increasing customer satisfaction, and working collaboratively to accomplish non-routine work assignments.

Regularly enlisting input from initially resistant stakeholders can provide valuable information to the improvement process.

When coaching Lean Six Sigma teams, I always encourage the members to invest the effort necessary to understand stakeholders’ perspectives. If the evaluation indicates a lack of support, some stakeholders may need to be added to the team so that the issues generating resistance can be investigated and resolved. Another option is to incorporate some stakeholders as adjunct team members/outside resources.

In either case, regularly enlisting the input and participation of initially resistant stakeholders can provide valuable information to the improvement process and demonstrate a sincere interest in taking the perceptions and experiences of those who will be affected by the change into account as solutions are developed.

Check Your Understanding

Here are some questions for you to consider regarding the use of stakeholder analysis. They provide a way for you to evaluate your understanding of this tool quickly.

- How can you create a positive environment when interviewing stakeholders that encourages them to express their views candidly?

- Suppose you had many diverse stakeholder perspectives. What approach and tools might you use to gather their input and summarize the key areas of resistance that would need to be addressed?

- How can hypothesis testing, regression analysis, and piloting be used to examine stakeholders’ perspectives and reactions to proposed changes?

Deborah Hopen has over 40 years of experience in total quality management, and has served as a senior executive with both Fortune and Inc. 500 companies. She is a Fellow of the American Society for Quality and is the editor of ASQ’s Journal for Quality and Participation.